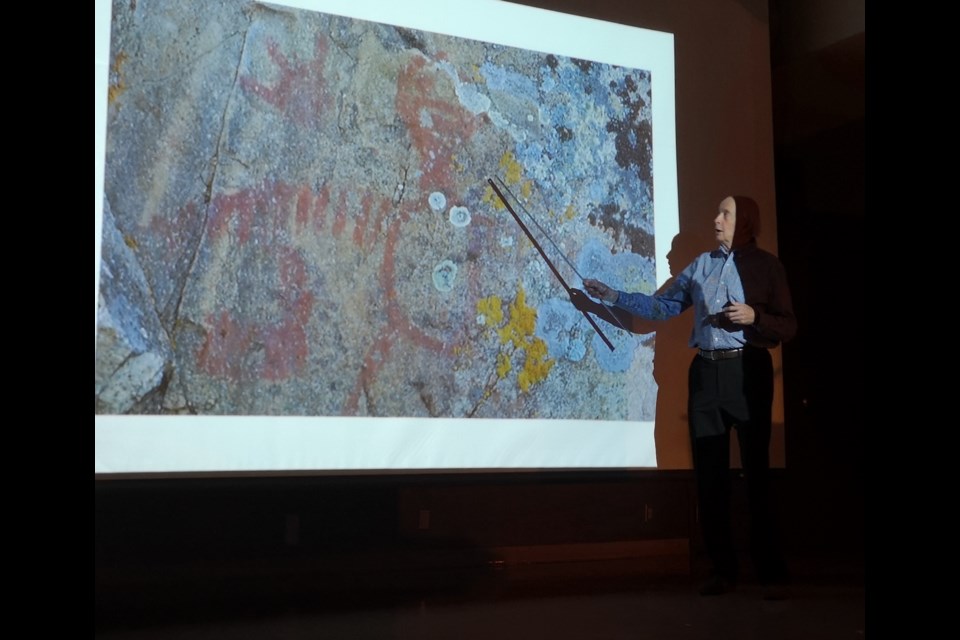

Guests attended a lecture at the Moose Jaw Public Library theatre on Aug. 28 to learn more about local Saskatchewan author Tim E. H. Jones. At the presentation he discussed his best-selling book, The Aboriginal Rock Paintings of the Churchill River.

When Jones travelled to northeastern Saskatchewan in 1964 and encountered his first rock paintings at Kipahigan Lake, he knew that he found his calling.

The rock paintings became the subject of his thesis paper back when he studied at the University of Saskatchewan. Based on this thesis, he published his best-selling book in 1981. When the book went out of print in 2005, it had sold more copies than any other book on the topic of Saskatchewan’s archaeological past. His book continues to be a major – if not the main published – guide to Saskatchewan’s northern rock paintings.

Jones explained the universal significance of rock paintings in his book. “Rock art is the most widely spread, diverse and ancient of all human creative endeavours,” he wrote. By learning more about these ancient works and the people who created them, we’re learning about some of the deeper aspects of human history.

His career took him north, and the scope of his work included Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and parts of northwestern Ontario. In northern Saskatchewan alone, he recalled taking at least 20 trips. “I haven’t seen all 70 sites in northern Saskatchewan either,” he said. “It’s a lot of territory to cover.”

Visiting these rock paintings is no easy endeavour. Many sites aren’t found on a map and can only be located with the help of Cree elders who live in the area.

“Many sites are found based on their information, and the site isn’t known to others,” Jones said.

Archaeologists have since worked with elders at the Lac La Ronge Indian Band and have formed a lasting friendship. “We’re interested in the health of the rock paintings in northern Saskatchewan,” said Jones. “The Lac La Ronge Band has put the weight of their assistance behind us.”

Larocque Lake stands out and translates into “little red ochre lake” in the Cree language. Its name comes from the naturally occurring red ochre pigment in the area, which is the most common pigment used in rock paintings worldwide. The pigment is made of silica and clay, and the deep, blood red colour from iron oxide holds symbolic and spiritual meaning.

To get there, one must drive up to Stanley Mission and meet with a local guide. The guide then takes them upriver by boat, and from a base camp there’s a lengthy hike before arriving at “a spectacularly scenic spot in Saskatchewan.” An optional flight takes around one hour and 40 minutes.

Studying these paintings is a race against time as natural forces weather and crack the rocks. To expedite the natural process, vandalism is a worldwide problem but also civic works, such as the 1947 Reindeer Lake dam project that saw a stretch of paintings flooded.

Some observers may feel the pictures are simplistic, but they are carefully and deliberately crafted, even going so far as to require a brush as some details are millimetres apart. For the painters, it’s all about the message and not about dry, technical mastery.

The interpretation of these paintings is debated, but archaeologists work closely with Cree elders to offer insights from Indigenous culture and belief. They are believed to depict dreams, visions, or ceremonies. “Even if you were present when the shaman performed the ceremony, you still wouldn’t understand,” Jones said, noting that the gap between cultures is significant.

“Anyone can interpret rock art; whether you’re right or not is another question,” Jones explained, further noting that a lot of the interpretation is based off speculation. Regardless, interpreters use references and look for recurring themes. “It doesn’t mean that we don’t know anything.”

The Canadian Shield acts as a great divider between style themes. East of the shield, paintings are singular and tend to stand alone; west of the shield and into Saskatchewan, paintings appear more frequently as groupings. Jones’ hypothesis is that climate plays a large role, as Saskatchewan’s long winter and dry climate may simply preserve a similar work far better.

Carbon dating is one method to determine the age of these works, but the process isn’t widely utilized as it’s prohibitively expensive. One site in Quebec had been tested so far, and the result was astonishing: the painting was over 2,200 years old, give or take 70 years. This finding helps estimate comparable works across the Canadian Shield.

Many resources can be borrowed from the Moose Jaw Public Library. Jones recommended three during his presentation:

- Indian Rock Paintings of the Great Lakes by Dewdney, Selwyn H.

- Canoeing the Churchill: A Practical Guide… by Marchildon, Gregory P.

- Spirit in the Rocks (DVD)

The presentation was supported by the Saskatchewan Writer’s Guild. Founded in 1969, the guild is a not-for-profit organization seeking to improve the status of writers in Saskatchewan, encourages their development, and seeks to improve both public awareness of and access to their works.

Jones’ career has spanned three decades, and his hope is to preserve these rock paintings for future generations and to promote a sense of respect for this form of art. He currently lives in Saskatoon.

To read his book, you can search the Palliser Regional Library’s catalogue at PalliserLibrary.ca or download a PDF version at https://harvest.usask.ca/handle/10388/etd-10182007-073337.

In response to some providers blocking access to Canadian news on their platforms, our website, MooseJawToday.com will continue to be your source for hyper-local Moose Jaw news. Bookmark MooseJawToday.com and sign up for our free online newsletter to read the latest local developments.