It was mid-September 1944 when the Allies launched a joint ground-airborne offensive called Operation Market Garden that they thought could help bring the Second World War to a speedier conclusion.

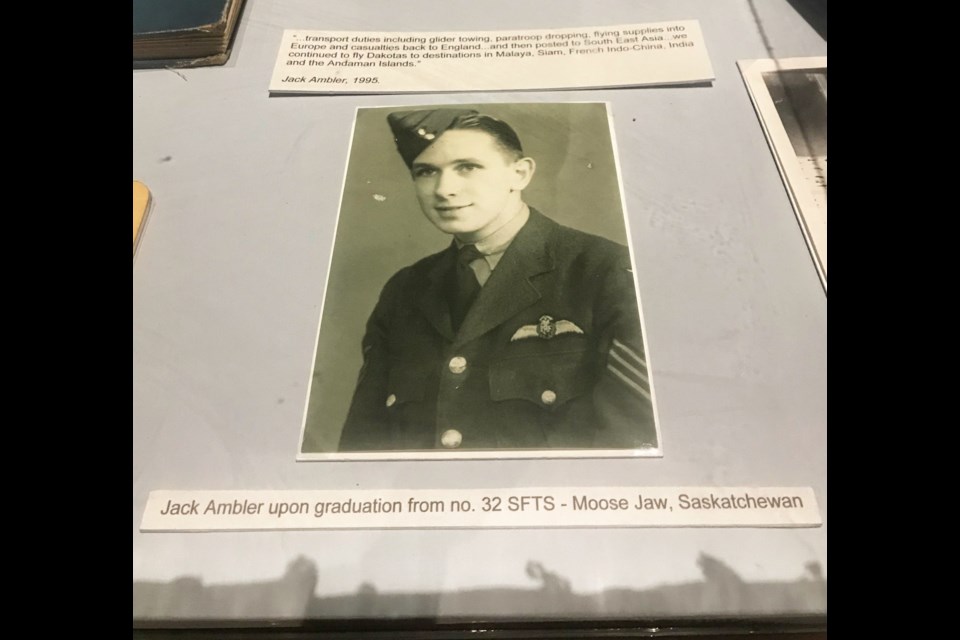

Tasked with transporting a group of British paratroopers into the Netherlands — whose goal was to capture the bridge in Arnhem — was Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot Jack Ambler, who had trained in Moose Jaw from June to September 1943.

After graduating and receiving further training on DC-3 transport aircraft, his first mission was on Sept. 10, 1944, when he and other members of 48 Squadron began delivering supplies to the newly-freed Belgian city of Brussels and nearby airfields.

On Sept. 17, Ambler’s crew took part in Operation Market Garden as part of an armada of aircraft towing Horsa gliders and carrying paratroops to Arnhem. However, their Dakota aircraft — dubbed “Oor Wullie” — had fuel trouble halfway across the North Sea, explained Ambler’s daughter, Jacqueline. They were towing a glider with a jeep, six men and a small field gun.

“Both engines cut out and they were forced to lose altitude and the glider had to release from the tow rope and go down in the sea,” she said. “They frantically worked on the fuel system wobble pump, and at about 500 feet above the sea, they were able to get one engine going and stay in the air.”

The transport crew managed to get their second engine running and, after ensuring the glider crew was safe in the water, returned to base and an unhappy debriefing.

By Sept. 25, the operation had failed and the British paratroopers were fighting for their survival. Ambler’s crew took part in two resupply missions to relieve the beleaguered troopers.

On the first mission, anti-aircraft fire hit Ambler’s transport plane — they were the first resupply plane to reach the city — and it lost an engine, but the crew managed to drop the supplies before heading back to base in England, Jacqueline said. During the second trip, an enemy fighter plane caused troubles for the transport crew, but they avoided any serious issues.

Ambler’s crew later learned that the supplies had fallen into German hands, as the enemy had overrun the drop zones and communications problems prevented the ground forces from providing an update about the changes.

Throughout the 10-day operation, 48 Squadron flew 111 sorties — more than any other Dakota squadron — and towed 52 gliders while making 59 supply runs. The unit lost seven planes, 14 men died, four were taken prisoner and 10 escaped and returned to duty.

Of the 11,920 British paratroopers who took part in Operation Market Garden, 1,485 died and 3,910 were evacuated across the river, leaving 6,525 as prisoners of war. Hence, the airborne part of the operation came to be known as “A Bridge Too Far.”

To the Far East

By August 1945, the war in Asia was coming to an end, but Ambler and his new crew were ordered to report to the Far East for further missions. They hitched a ride on a Stirling bomber, which took them from England through the Middle East to India, before they ended up in Mingaladon, Burma.

Their goal in the Southeast Asian country — now known as Myanmar — was to fly supplies into the jungles by dropping bags of rice to the starving people hiding from Japanese soldiers.

Life at the airbase was anything but comfortable. Crews had to beg, borrow and steal supplies to create suitable living, eating and washing venues. Ambler’s crew built their bathtub by creating an earthen berm lined with black tar paper. They also constructed an adjacent shower by supporting a two-gallon can on four bamboo poles and piercing the bottom with a nail.

Meanwhile, the Sergeant’s Mess was a bamboo-walled dining area with no insect screening, which gave mosquitos, flies and other unrecognized creatures full access to the food.

The Moose Jaw-trained pilot’s first flight out of Mingaladon was a check flight to Bangkok, Thailand. The crew returned to the airbase with several former POWs who had worked on the infamous Burma Railroad — also known as the Bridge over the River Kwai. This was the first leg of their journey back to England.

“… he told me he couldn’t figure out how any of those poor men survived, as they were skin and bones when they were brought on the plane … (it was) a sight he said he would never forget,” recalled Jacqueline.

Caring for others

In February 1946, Ambler’s crew and others made weekly flights to drop bags of rice to the starving hill tribes in the low mountains between Burma and Thailand. The planes made several passes to drop the rice bags, each of which weighed 80 lbs; a full planeload would usually drop 5,000 lbs.

Meanwhile, each crew had to regularly flight test aircrafts grounded for maintenance or repairs. During one test, Ambler’s crew performed the usual test procedures when they collided with a large bird. It hit the root of the starboard wing, which began vibrating immediately.

The crew made an emergency landing and taxied to the parking area, where airframe mechanics assessed the damage. The issue was a break in the main spar of the wing, so repair required a complete wing replacement.

One of Ambler’s final responsibilities in Southeast Asia was in March 1946, when he had the honour to have Jawaharlal Nehru as a passenger on a flight to Singapore, Jacqueline said. Pandit Nehru, as Ambler knew him, eventually became prime minister of a newly independent India later that year.

Ambler finished in Burma in March, and by July 1946, he was back in England after a 29-day boat ride. He eventually married Anastasia (Nel) Berbenak — a woman he had met at a dance in Moose Jaw — in October 1947.

Community service

After settling in Regina in 1967, Ambler became involved in the United Way for 35 years, helped found the South Saskatchewan Community Foundation, and volunteered for numerous charitable causes throughout his 90 years.

Although he never sought recognition for his volunteer work, he received many awards for these efforts, said Jacqueline.

Some awards he won included the Saskatchewan Centennial Medal, the Canada 125 Commemorative Medal, the Governor General’s Caring Canadian Award, the Memorial Medal of Honour from the Netherlands’ Airborne Commemorative Foundation, and the Minister of Veterans’ Affairs Commendation for Volunteer Work with Veterans, which hangs at 15 Wing airbase.

He also received the Saskatchewan Volunteer Medal in 2009 and the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012.

“He always felt that the veterans were important as it was because of them we have the freedoms we hold dear,” his daughter said.

Ambler was also part of the Saskatchewan War Memorial Project committee that designed and built the Second World War memorial, which sits on the provincial legislature grounds.

Returning to Europe

Ambler returned to Europe several times to participate in Liberation Day ceremonies held each May in Holland. During the 65th anniversary ceremony in 2010, he was presented to the Queen of Holland and asked to lay a wreath on behalf of veterans.

In 2012, Jacqueline accompanied her father to Europe, where they drove to places in the Netherlands, Belgium and France where he had flown during the war.

“It was a great trip, and because dad wore his medals during the days marking the liberation, he was treated like royalty,” she recalled.

During a trip to the Hartenstein Museum, the daughter of the woman who w known as the Angel of Arnhem — for caring for wounded Allied paratroopers and hiding them in her home — recognized Ambler from a previous trip and invited him and Jacqueline to her home to see where her mother had hidden the soldiers.

At trip’s end, Ambler and Jacqueline visited the pilot’s former crewmen in England, who had remained friends after the war.

“I don’t think I’ve ever laughed so much as when they were retelling some of their escapades during the war,” she added.

Jack Ambler died in 2013 at age 90 and resides in the Rosedale Cemetery with his wife.