Edna Banks was a young woman from the bustling city of Toronto who was keen on marrying her beau, Wilf, who had travelled to Moose Jaw in 1910 to homestead.

She decided to follow her future husband and jumped on a train west, but encountered difficulties with this mode of transportation and faced unique situations before reaching Saskatchewan.

Getting married was memorable for Banks, as was her first overnight stay at a stopping place, as she and Wilf travelled by horse and wagon to their homestead. Her first glimpse of her new home was also an unforgettable experience, particularly her disappointment with its rustic flair.

Banks’ written recollections would probably have stayed buried in the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan if it were not for Regina-born author Sandra Rollings-Magnusson.

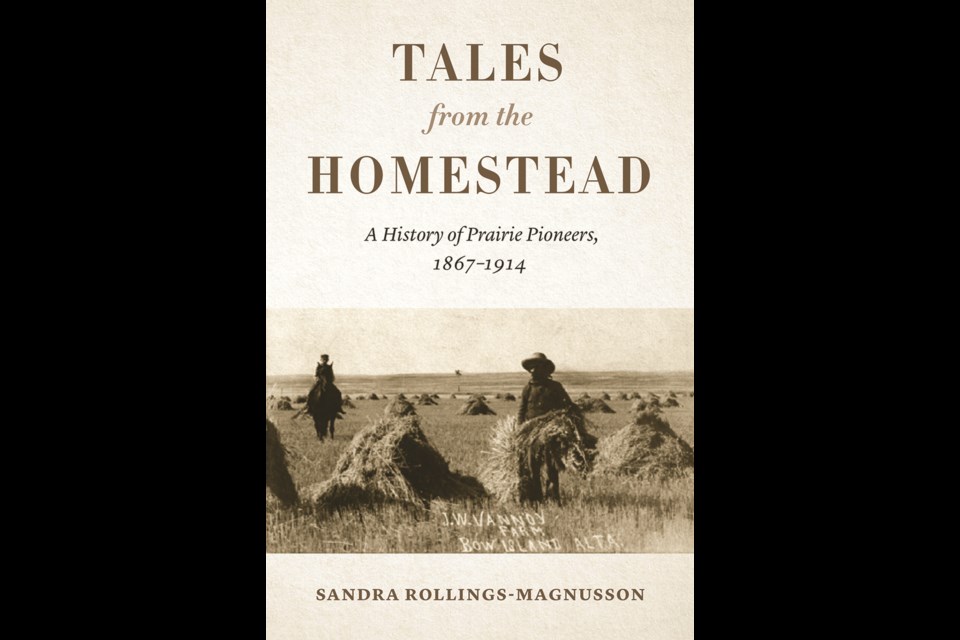

Her recent book is Tales from the Homestead, a collection of 36 first-person accounts of Prairie homesteaders who came in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and lived in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Rollings-Magnusson used archival material to highlight the stories of early European immigrants who arrived in Western Canada. She shares their challenges and triumphs of Prairie life, including famine, loss of livestock, community celebrations and neighbourly help.

The book also includes stories of surviving near starvation and natural disasters, navigating the difficult immigrant process, building a sod home and establishing a farm, dealing with mosquitos and black flies, and adapting to a new country.

The MacEwan University sociology professor has studied Western Canadian homesteaders for more than 30 years. She has written numerous academic articles, lectured about pioneer living, and penned two books about pioneer times in Saskatchewan.

Saskatchewan’s early history has been Rollings-Magnusson’s area of focus for years, she explained, because her grandparents were homesteaders and she visited them regularly as a child, she collects period antiques, and she has spent decades digging through archives for academic research.

“It’s kind of my whole life … ,” she laughed. “I just really enjoy it.”

Tales from the Homestead occurred because of all the archival material Rollings-Magnusson had collected during the past 30 years, she explained. While her previous writings were about statistics and numbers, she also found stories, letters, memoirs, autobiographies, and reports that the homesteaders wrote that she filed away.

“I have almost a mini archive at home (because) I’ve photocopied so many materials,” she said. “And each of those stories can be used in different ways or different fashions.”

It took Rollings-Magnusson about two years to complete this latest publication. There are several stories in the book that she likes, such as horse thievery in Alberta.

The story goes that Montana-based homesteaders came north and camped for the night, only to find their horses missing the next day. After three days, a group of riders came claiming they had found the horses, but the homesteaders had to pay to get them back.

“So since you’re stranded and isolated in the middle of nowhere, I guess you have to pay,” she laughed. “But those (riders) are the ones who stole them in the first place.”

A happier story focuses on community dances and families coming from 25 miles away to participate. Many were happy to see others since they lived isolated lives on their homesteads. Dances usually went until 7 a.m. since people had such a good time.

“They took such joy in these events. They were few and far between … because otherwise, their life was filled with hardship and toil and anguish,” said Rollings-Magnusson.

Rollings-Magnusson noted that many homesteaders often wrote to stay busy. It’s also how they entertained themselves, especially during long, cold winter nights.

By participating in the provincial government’s questionnaire project about early pioneer life in the 1950s, the homesteaders also contributed extra pages with their thoughts.

There was one recurring theme in the surveys that Rollings-Magnusson found interesting.

“… often they would say that they’re doing this for the purpose of they don’t want to be forgotten,” she said. “They were hoping that someday their stories would come to light, that the homesteading era — the efforts they put into working the land, the hardships they experienced, the good times they experienced — would not be forgotten by future generations.

“And actually, that’s why I write on this era. I hope to bring a voice to them so their stories aren’t forgotten … ,” she added. “That homesteading era will never again occur. That was kind of a unique period of time.”