Winnipeg-based author and photographer Steve Van Vlaenderen has always been enthusiastic about automobiles and their histories, which is why he was in Moose Jaw recently viewing a rare 1920s Derby car.

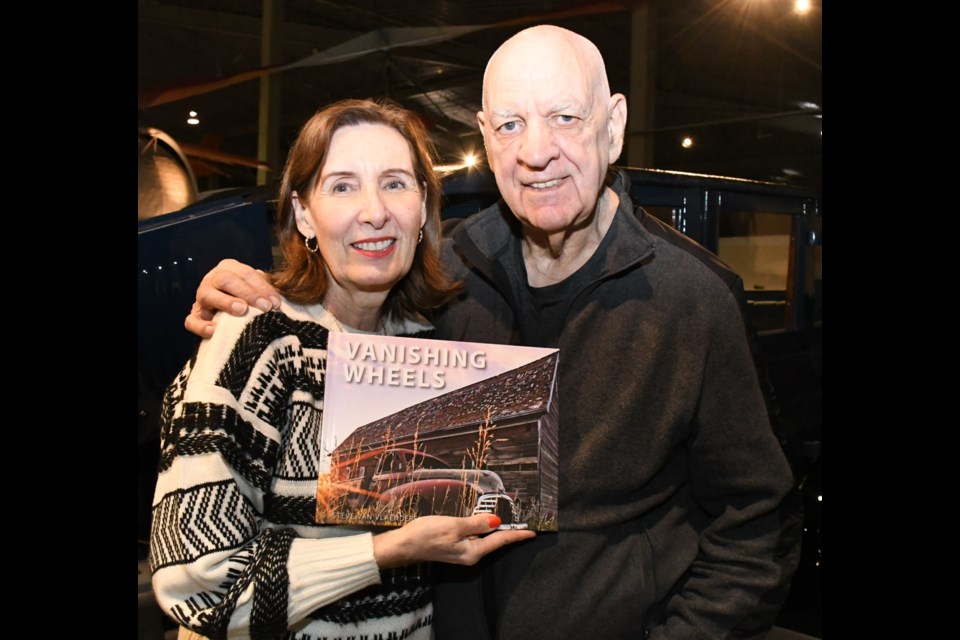

Van Vlaenderen conducted a photo shoot at the Western Development Museum on Jan. 25 with the help of his spouse, Darlene Hildebrand, and Dave Burba, president of the Road Rebels Car Club in Brandon, Man.

Members of the Saskatoon Antique Auto Club (SAAC) were also present since the club restored the vehicle a decade ago.

Photographing old vehicles is a hobby for Van Vlaenderen, a car aficionado and former semi-professional racer who once competed against Quebec legend Gilles Villeneuve. The retired entrepreneur recently released the book “Vanishing Wheels,” a homage to derelict cars and trucks dotting the Prairie landscape.

Van Vlaenderen and Hildebrand spent three months in the summer of 2021 driving 16,000 kilometres across Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, tracking down those “relics of yesteryear” to photograph.

The author is donating all sales proceeds to Parkinson Canada to fund research into Parkinson’s disease, with which he has lived for 13 years.

In fact, before the pandemic struck and his symptoms worsened, Van Vlaenderen and Hildebrand had sailed their 31-foot sailboat more than 2,800 kilometres across the Great Lakes to raise awareness about the disease.

“Vanishing Wheels” can be purchased from McNally Robinson in Saskatoon.

A new project

After completing his book, Van Vlaenderen began looking for another project when he heard about “The Winnipeg” car. That caught his attention, so he began looking for one to photograph — and learned more about the vehicle’s incredible backstory.

He explained that he is “spending every waking moment” researching this vehicle because he is fascinated and intrigued with how Winnipeg manufactured its own car in the early 1920s. He has also become “entrenched” in the automobile’s history — the story is “indicative” of Western Canadian perseverance — and has agreed to write an article for the Manitoba Historical Society.

The Winnipeg car company

According to the available facts, around 1920, four investors created an automobile company in Winnipeg called Winnipeg Motor Cars Ltd.

The men purchased a factory and built a pilot model for promotional purposes. The vehicle was actually a “re-badged” — re-branded — Hatfield Model A-42 tourer from Sidney, New York.

The Hatfield was shipped in pieces — that method avoided heavy import taxes — to Winnipeg, reassembled, and fitted with a company radiator emblem and hub caps. Additional features were a set of chains for the wheels and a non-burstable radiator.

The investors then promoted the car with the slogan, “As good as the wheat.”

Still lacking money to build cars, the four investors imported another car, this time a Davis vehicle from Richmond, Indiana. The American company provided enough parts for 10 tourers, which again featured Winnipeg badges and hub caps.

Money for the vehicle assembly — $410,000, or $7.3 million today — was provided by a syndicate headed by George Shutler. These Davis-badged vehicles were re-branded as “The Winnipeg.” The facts show the company likely produced six cars.

Going under

Although the 1920s were dubbed “The Roaring Twenties” because of how prosperous society was after the First World War, Winnipeg was in a recession, said Hildebrand. Furthermore, The Winnipeg was supposed to be a luxury vehicle, so the company sold it for three times the cost of comparable vehicles.

It was likely due to the exorbitant cost — and the fact employees and creditors wanted money owed to them — that the company “went under” in 1923. However, that didn’t stop Louis Arsenault, one of the four original investors, from starting another car company.

The Saskatoon car company

Arsenault took one of The Winnipeg cars to Saskatoon, where he found investors willing to contribute $440,000 — $7.7 million today — to start Derby Motor Cars Ltd., which operated from 1924 to 1927.

Rather than build cars, Arsenault imported American-built Davis cars, changed the nameplates to “Derby” and added Derby tire covers. Conversion and assembly took place in either the former Marshall tractor factory on 11th Street or in a meat packing plant.

The Derby boasted having plenty of passenger space, had a heavier body for better handling and possessed a six-cylinder engine when most cars only had four cylinders.

According to surviving records, the company sold 31 cars before the venture folded in 1927, with the original plan of building 50.

A slick salesman

Hildebrand described Arsenault as an “excellent salesperson” who took an idea and convinced people that these companies would be money-making ventures. However, both initiatives failed — “They didn’t build for the market” — which she noted is typical for many startups.

Despite his research, Van Vlaenderen was unable to determine why Arsenault brought a Derby car to Saskatoon, something Hildebrand mentioned during the interview. Fortuitously, SAAC members indicated the man was from The Bridge City and came home after the failed Winnipeg experiment.

Arsenault initially travelled to Manitoba because that city was bigger than Saskatoon and was expected to be a major transportation hub like Chicago, the SAAC members said. However, the opening of the Panama Canal in August 1914 — right as the First World War erupted — destroyed that idea.

“It’s a fascinating Prairies story,” Hildebrand said. “It’s a story of idealism. They tried, but it failed.”

Further research

Van Vlaenderen said he is halfway through his investigation into the Derby car and has spoken with people — such as auto restorers — in the U.S. to acquire more information.

While he has found most information from newspaper articles and from people who “know” things, he also plans to search the provincial archives in Saskatchewan and Manitoba for official company documents. This will help clarify whether the Saskatoon company planned to build 50 cars or the “folklore” amount of 500.

“I think (the Derby is) remarkable. It’s a piece of history that is preserved for generations to come … ,” Van Vlaenderen said, noting Arsenault was ahead of his time. “Each vehicle in this museum has a story. And we can’t forget those stories. That’s what makes these cars valuable.”

Said Hildebrand, “It’s just been fascinating to think that the Prairies were involved in automotive history this way … . It’s Prairie pride.”