Vimy Ridge was considered one of the more impregnable defensive networks on the Western Front during the First World War, a position that the French and British failed to capture despite many repeated attempts.

The Germans transformed Vimy Ridge into a heavily fortified system of tunnels and trenches in October 1914, defended with an arsenal of machine guns and artillery pieces. After three years of unsuccessful assaults, hundreds of thousands of British and French troops had died and failed to capture the ridge.

At about seven kilometres in length and culminating at an elevation of 145 metres (476 feet), Vimy Ridge provides a natural unobstructed view — great for defenders — for tens of kilometres in all directions.

The Allies gave the upstart — but effective — Canadians the mission of liberating the ridge from the Germans. After much preparation and rehearsal on a mock ridge, the Canucks were ready to take it to the enemy with a new strategy and newfound drive.

Making history

On a cold Easter morning at 5:30 a.m. on April 9, 1917, in northern France, all four divisions of the newly formed Canadian Corps — composed of 100,000 men fighting together for the first time — jumped out of their trenches and made their way — under the umbrella of a 1,000-gun creeping artillery barrage — uphill through sleet, mud and machine-gun fire.

The Canadians captured most of the ridge that day, but it took until April 12 to overcome the final hurdle: capturing Hill 120, also known as “the pimple.”

The cost for the small army was considerable: 3,598 soldiers died and 7,004 were injured.

Moose Jaw connections

Research shows at least 39 soldiers who died at Vimy Ridge were from Moose Jaw and area or enlisted here.

Pte. William Johnstone Milne was one of four Canadians to win the Victoria Cross, the highest military medal in the British Empire. He was killed on April 9 at age 24.

Other soldiers such as Edmon Francis Mittelholtz survived the battle and returned home in late 1917. He was born on May 10, 1896, in West McGillivray, Ont., and later moved west to Saskatchewan to work as a farmer,

He enlisted in Saskatoon on Dec. 18, 1915, and was attached to the 96th Battalion (Canadian Highlanders). The 92nd Battalion (48th Highlanders) later absorbed the 96th Battalion in 1916. The 92nd was known for its soldiers wearing kilts in the trenches.

“He never talked to us about war, but if a First World War veteran came over, we would lay in bed and listen to the stories he would talk about with the other veteran,” son Vern recalled. “Our bedroom was right next to the living room, so we heard everything that went on.”

While Vern couldn’t recall a specific story his dad told about fighting at Vimy Ridge, he does remember his father talking about the August 1917 Battle of Hill 70.

“He (Edmon) said after the slaughter at Hill 70, after the Newfoundlanders were slaughtered and he had to crawl through the corpses, the only reason his unit got up the hill was because the Germans ran out of ammunition. That was his story,” added Vern.

Letters from the battlefield

Meanwhile, Lance Cpl. Harry Alexander Chalmers was born in Ontario but enlisted in Saskatchewan. He wrote several letters to a Saskatchewan woman about his war experiences, including preparing for Vimy.

On March 18, 1917, he said he witnessed “great preparations” leading up to the battle. “There are miles of transport wagons and motor trucks on the roads all the time. The work is mostly done at night. It’s wonderful how a man gets around in the dark.”

In a letter written on April 11, 1917, Chalmers described the scene from the front line.

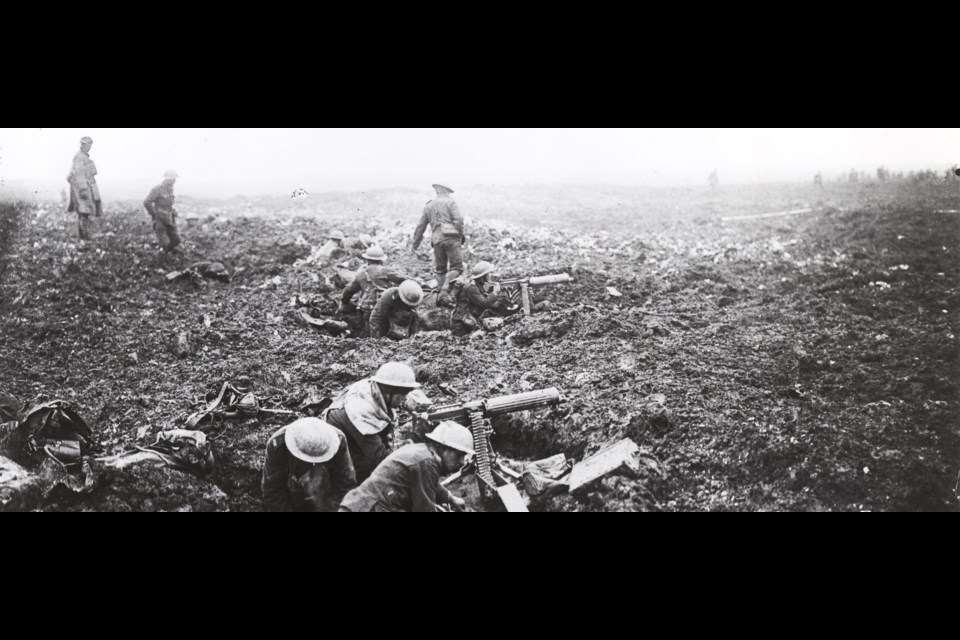

“Well it’s some sight to see a battlefield after the thing is over,” Chalmers wrote. “There is not a square inch of ground (that has not) been touched by shell fire. It’s just a mess of shell holes, barb wire and torn trenches. The most awful mess I ever seen. You can’t realize what it’s like.

“The front line and supports and third line of the Germans was pounded into a pulp. Such a noise I never imagined in my life. Bedlam was sure let loose … . The sights around the field are terrible looking. I hope I don’t witness anything like it again.”

Up close with the enemy

Chalmers also wrote that he’d “never seen such tickled men as some of (the German soldiers) were to be taken prisoner.”

“The (Canadians) began to collect souvenirs and even cut the buttons off (the German prisoners’) clothes. They were quite willing to give up anything,” he reported. “After they got back of our lines some of them made themselves quite useful, helped with the wounded and carried water. They are a motley looking bunch.”

“It takes a few lessons like this one to show him who’s who but when a fellow sees sights like this one it seems funny that humanity can’t get along without war,” Chalmers added. “There’s room for us all on this globe yet without this slaughter.”

Of the battalions that fought at Vimy Ridge, four were from Saskatchewan: the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles, the 5th Battalion, the 28th Battalion and the 46th Battalion. Over subsequent years, the first two have evolved into the North Saskatchewan Regiment (based in Saskatoon); the 28th into the Royal Regina Rifles; and the 46th into the Saskatchewan Dragoons (based in Moose Jaw).